“‘These people are dangerous and insane,’ Hemmings said. ‘The polarities, the constants, the projections, and so on, all of this would indicate that within a very short amount of time, even by our standards, they will pose a real menace. We have to stop this, of course. Onward! We must protect our interests and so on. Unity!’” [10]

In this series, I read and write about an older science fiction novel, from a haul of books I own. In this entry, we have Overlay by Barry N. Malzberg.

PUBLISHING:

Overlay, Barry N. Malzberg (141pgs); Lancer Books, USA, 1972; NEL Books (New English Library), UK, 1975.

THE PLOT:

Aliens have seen our world and have decided: we must be eradicated. It is the Galactic Year 453 (1978 in Earth years) and they have decided humanity is far too dangerous to let live; our technology and very personalities have become a threat. So the Bureau has hatched a plan…

The unnamed narrator of Overlay has been personally tasked with psychically manipulating four humans to bring about a cataclysm. All four of them are horseplayers (people who bet on horse-races), and each represents a stereotypical kind of gambler: Mary, who is a caustic elderly woman who faces destitution whilst waiting to defeat her losing streak; Tony, a horse trainer who proves difficult to manipulate; Gardner, whose addiction is fully realised but superstition and passion keep him in the game; and Simmons who, as the blurb explains, is the “most important human on the planet” – a real loser who can’t catch a break. Through them, the narrator is architect to an apocalyptic plan which would destroy all of humanity and free Earth from our seemingly diabolical hold.

SO, OVERLAY…

Barry Malzberg chooses to open the novel with an excerpt taken from another book: Howard E. Rowe’s Aqueduct and Santa Anita on $105 a Day – a book of short stories published in 1970 about horses and horse-racing. The quote regards a horseplayer whose inner voice speaks with conviction during the race, but realises too late it was wrong in its predictions. This sets up a particular atmosphere for the novel: the human characters act similarly when betting (their inward and outward cursing, their disbelief in loss, and their subsequent resignation), but the quote also echoes the ways in which the narrator influences the four as well. He is often a voice, accepted by some of them as a sign of their waning sanity, whilst sometimes appearing physically, almost like an hallucination, to encourage them in making certain bets; he promises tips but always edges them towards failure. The narrator is that voice which the bettor hears, which urges the desperation to win. Following this quote is another: a strange diatribe which reads like a surreal prayer, asking for forgiveness for their betting sins. This becomes important later in the novel but sets up recurring themes here around betting: the superstition surrounding it, and the dedication the players feel, might not always make sense to the observer.

To the aliens, the horseplayers perfectly represent a nonsensical dichotomy which exists in humans but baffles our alien visitors. Our “dualism” [103] makes little sense to them in their cold practicality: we adhere to logic and scientific prediction, yet we also bow to superstitions and irrational fantasies in equal measure – and no one does this more, the aliens believe, than the horseplayer. The horseplayer reads betting tips written by supposed professionals who base their predictions on the horses’ past performances in previous races, but at the same time they believe in the almost metaphysical power of beating a losing streak through their own superstitious feelings and beliefs, and that the one great win is always on the horizon ready to transform their lives. The narrator often admits that despite his professionalism he is taken aback by humanity’s unpredictable nature [85-86] – we are at odds with the aliens in this novel, who are cold, dedicated to their cause, lacking empathy, and cruelly manipulative, yet in the most bureaucratic way possible.

Despite humanity being viewed as this diabolical creature which must be stopped, humanity appears largely benign here; there is no focus by the aliens on war or our tendencies to cruelty throughout history (though perhaps this is implied), but instead humanity here is represented by these four individuals who struggle to break free of their addiction and more often than not are the butt of some pretty darkly comedic situations. Humanity appears flawed, yes, and selfish, sure, but not as evil as some other SF works might try to depict us. Instead, the aliens here come across as (occasionally comically so) coldly efficient, and it is they who appear more deadly and dangerous and incredibly cruel; their desire to destroy us seems a bit…harsh? The narrator often observes his subjects and sometimes tries to muster some empathy for them – yet it often comes across as weak or misplaced. Despite their dealings with creature’s psyches (both humans and animals are easily controlled by them), they seem to lack a deeper understanding of why people act the way they do. Rather than ask questions, they’d prefer to destroy. When our narrator questions Simmons why he sticks to betting when it has done nothing but ruin his life, Simmons replies that despite all the pain, horseplaying was very “beautiful.” [125-126] Unsurprisingly, our narrator is taken aback by this. In fact, the narrator does make some astute observations: “’The nature of you people is to put up with anything, the worst horrors, as long as you could be assured there is some meaning to it.’” [124] This observation almost sounds like an insult, and yet it perfectly reflects humanity’s need to analyse and understand: something our alien visitors do not quite grasp. If so, does this mean the aliens live a meaningless life themselves? In their rationale and practicality, are they perhaps lacking meaning in having made their worlds so simplistic? There’s a lot of ways a reader can analyse this work…

Though dystopic in nature, the novel has fleeting moments of black comedy; the ‘loser’ nature of the characters is certainly heightened, and is often sympathetic. Mary, in particular, is very selfish and melodramatic, especially when dealing with her adult son, who refuses to pay for her any more, but in such an exaggerated way that it comes across as darkly comical. The setup of the alien/human relationship itself is humorous too – the aliens view horseplayers as the key to the cataclysm, viewing them as a specific subsection of human life and it is specifically their weird dualism which leads to all of humanity’s downfall. From these four horseplayers, the aliens create a bizarre version of the four horsemen of the apocalypse. This latter image also plays into some of the more surreal and unpleasant images which lightly dot the novel, particularly in the third act. We see small glimpses of the apocalypse due to come and these images are surprisingly gory and disturbing compared to the majority of the novel, which is far more observational and gentle in tone.

Malzberg’s style here is also noteworthy; beautifully written and with a purposefully complex command of language, he perfectly depicts the narrator, though we know very little really about his life or appearance. This work also fits into the soft science fiction subcategory – and a favourite of mine – in which psychological themes take precedence over out-and-out scientific fact or theory; this novel is clearly more concerned with the psychologies of its characters and the ways in which something alien tries to understand them, than how the telepathy works or the in’s-and-out’s of the cataclysm itself.

This latter theme highlighted (well, to me, at least – this book is ripe for literary analysis) how entrapped the characters are – both human and alien alike. The human four are caught by their love for betting: trapped financially, socially, psychologically… Their horseplaying controls them as much as the narrator’s telepathy does. Yet so too are the aliens flawed: trapped in their lofty views of the universe and their inability to understand their subjects; despite their inherent psychological talents, they struggle to understand the things they claim to be able to control. The narrator’s mission takes precedence above all else; he is as controlled and monitored by the Bureau as his human subjects are by him.

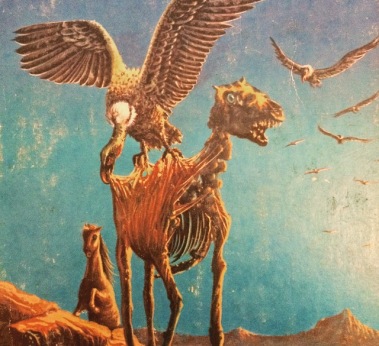

THE COVER:

Unsurprisingly, the cover art to this novel is somewhat eye-catching. In fact, it might be one of my favourites from the whole bundle! It depicts a desolate landscape in which two horses roam – however, the horse in the foreground has had its bones picked nearly clean by the swarm of vultures pursuing it. Meanwhile, a living and pristine horse in the background seems to follow or is perhaps ready to overtake. It’s a cover which conjures all sorts of questions and you’d be forgiven for wondering what this has to do with a novel largely set in New York City in the 70s. Ultimately, this art does fit the subject in retrospect: the horses reflect the sport of the novel, but the picked clean horse brings to mind the dystopic and hopeless natures of the characters: they, too, are being picked clean by their addiction, targeted and whittled down by the alien which manipulates them. It also symbolises the endgame the aliens have devised: leaving Earth bare of human life. There’s plenty of meaning to be gleaned from this surreal and horror-infused front cover, and, god, I love it… Though not credited anywhere on the book (and, man, did I search), the artwork seems to be credited to Ray Feibush (1948-1998, Liverpool) who created a lot of cover artwork for the New English Library editions (yes, this book is one of them) – so hopefully this is correct. A quick search online shows numerous similarly styled works credited to him – and this cover also appears there too. He also did illustrations for some books and LPs, and seemingly moved between the UK and US during his art career. Check out some of his other works, they’re really amazing!

THE AUTHOR:

Barry N. Malzberg (b. 1939, New York City) is an author and playwright, with an impressive canon of science fiction novels and erotic fiction (under a pseudonym). His works in SF are often described as dystopic and a quick search finds that he is also linked to “recursive science fiction” (SF about SF). Known for his run-on sentence style, his works often have a psychological theme too. Beyond Apollo (1972) is an award-winning novel by Malzberg (if you look closely at my copy, it mentions its winning a John W. Campbell Award), which is still widely in print and is often used to define his particular style in SF – definitely going to have to check this out when I have the chance! Other themes he is linked to surround bureaucracy, metaphysics, and psycho-sexual content. His science fiction novels and short stories were published well into the 80s and 90s and a number of short story collections by him are still available, with one recently being published in 2013. I highly recommend you check out his works, if not Overlay itself; many of his more popular works have both physical and digital copies available.

AVAILABILITY:

Overlay is seemingly out of print at the moment (both paperback and hardback editions link you to second-hand sales instead), but thankfully there are many places to get your hands on this particular edition quite cheaply. Alternatively, however, you may want to purchase this on kindle, where it is currently being sold for only a few pounds, on amazon. There is also the opportunity to buy the audiobook (recorded by Blackstone Audio, Inc., in 2014) and there appears to have been a CD release of this recording too (though this is more pricey). Kindle proves once again to be a great area for some science fiction to get a new lease of life, so do check out this great novel if you like the sound of it!

Next Up: Unwise Child (1962) by Randall Garrett! See you in a few weeks!

I fellow Malzberg fan! I’ve reviewed thirteen (I think) of his novels and collections on my site. I haven’t read Overlay yet.

LikeLike

I wrote in haste, it should read “Hi fellow Malzberg fan”!

LikeLike

Hello! You should definitely give ‘Overlay’ a try – I certainly need to read more of his works! I’ll be sure to check out your blog too!

Many thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

My favorite is Revelations (1972). Have you read it?

LikeLike